Average true range volatility (ATR) is one of the simplest yet most useful indicators, helping traders clearly understand market volatility before placing a trade. In fact, many stop-loss hits happen not because you misread the trend, but because your stop was “too tight” relative to volatility at that time. In this article, Pfinsight.net will walk you through what ATR volatility measures and how traders can adjust stop-loss placement to match different volatility conditions.

- What is the ATR Indicator and how it works in trading

- RSI divergence and how it signals potential trend reversals

- MACD histogram: How it reveals shifts in market momentum and the signals MACD doesn’t tell you

Why fixed stop losses fail in different volatility regimes

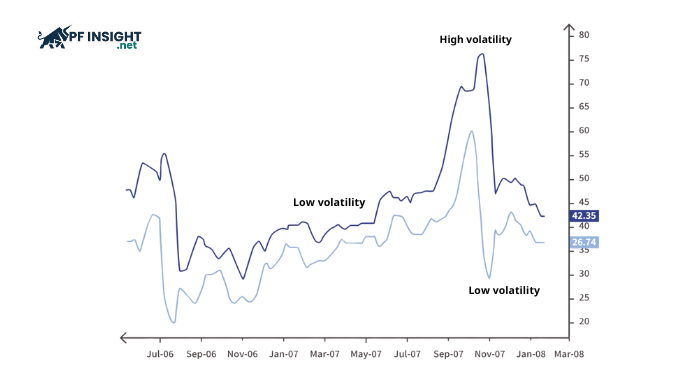

One of the most common mistakes traders make is using a fixed stop loss (for example, always 20 pips/50 pips or 1%) across all market conditions. The problem is that volatility is not constant sometimes the market is calm, while other times it becomes highly volatile due to news events, thin liquidity, or breakouts. When you keep a fixed stop loss while volatility changes, the stop no longer matches price behavior, leading to repeated stop-outs or distorted risk/reward.

Market noise changes

“Market noise” refers to the small fluctuations and wicks that naturally occur as price moves. This noise can increase significantly when:

- There is major news or during session transitions (open/close)

- Liquidity is low and spreads widen

- Price enters a sideways phase or a high-volatility regime

When noise changes, the price’s vibration range changes as well. This is why a stop loss level that worked well in one phase can become too tight in the next. Professional traders often view volatility as the market’s “background vibration,” and a safer stop loss must sit outside that vibration range.

Stop too tight vs too wide outcomes

When a stop loss does not match volatility, it usually leads to two situations:

Stop too tight

- Price only needs a small shake or wick to hit the stop

- You get stopped out even though the trend is still correct

- Your psychology gets worn down because “I keep reading the direction right but still lose”

This often happens when volatility is high but the stop is still set using a fixed habit.

Stop too wide

- A wider stop increases per-trade risk

- Risk/reward becomes less attractive and harder to stay disciplined

- It can lead to overconfidence or “taking a wider loss” without any strategic reason

This usually happens when volatility is low but you still use a wide stop “just in case.”

In short, a fixed stop loss only works when volatility is stable, while the market shifts volatility regimes over time. That is why many traders switch to ATR-based stop placement: it allows the stop loss to “flex” with real volatility, instead of forcing a fixed number onto every situation.

What ATR volatility really measures

After understanding why fixed stop losses often fail when volatility changes, the next question is: how can you measure current volatility to place a more appropriate stop? This is exactly where the Average True Range (ATR) becomes useful.

ATR measures volatility, not direction

The most important thing to remember is that ATR measures volatility (the size of price movement), not trend direction. That means:

- ATR rising → the market is swinging more strongly, with larger candle ranges

- ATR falling → the market is calmer, with a narrower trading range

But ATR does not tell you whether price will go up or down. Therefore, ATR is not a tool for directional entries. It is a risk management tool, especially for stop-loss placement and position sizing.

Why “true range” matters (gaps and real movement)

ATR is built on the concept of True Range (TR), which represents the market’s “real” price range. Unlike a simple range (High – Low), True Range also includes situations such as:

- Price gaps compared to the previous candle

- Volatility caused by session opens/closes

- Abnormal price jumps

Because of this, ATR reflects real market volatility more accurately than just looking at candle size.

Quick interpretation: higher ATR = wider stop

Traders often use ATR as a gauge to quickly answer: “On average, how much does price typically swing per session/candle?”

If ATR is high:

- The market swings widely

- A fixed-distance stop loss is more likely to get hit

- You need a looser stop or smaller position size

If ATR is low:

- The market swings less

- An overly wide stop reduces risk/reward efficiency

- You can place a more optimal stop and improve RR

In short, ATR does not help you predict price direction, but it helps you set a stop loss that matches current volatility, reducing stop-outs caused by market noise.

ATR calculation essentials (the only formulas you need)

To use Average True Range (ATR) volatility for stop-loss placement, you do not need to memorize too many formulas. You only need to understand two things: what True Range (TR) is, and how ATR is calculated from TR. Once you grasp this logic, you will understand why ATR reflects “true” volatility rather than just the size of a single candle.

True Range (TR): the 3-part volatility formula

True Range is defined as the maximum value (max) of the following three measurements:

- High − Low

- |High − Previous Close|

- |Low − Previous Close|

In simple terms:

- (High − Low) measures the candle’s intraday range

- The other two components allow TR to capture gaps or sudden price “jumps” relative to the previous session

- That is why ATR is called the “true” range: it does not ignore important volatility caused by gaps or jumps.

ATR formula: how true range becomes average volatility

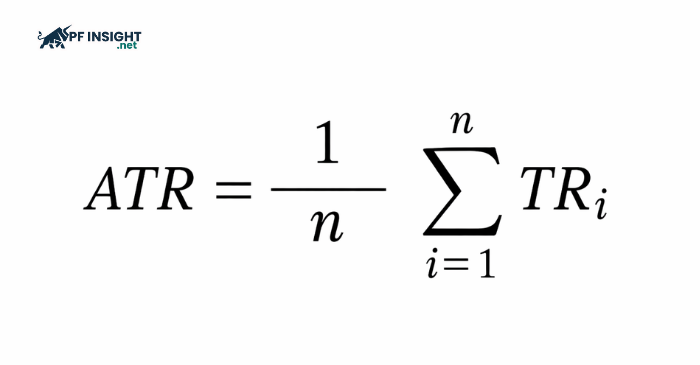

After calculating TR for each day/candle, ATR is simply the average of that TR series.

The most common setting is ATR(14), which represents the average volatility over the most recent 14 candles.

There are two cases:

- When there is no previous ATR value

The initial ATR is calculated as a simple average:

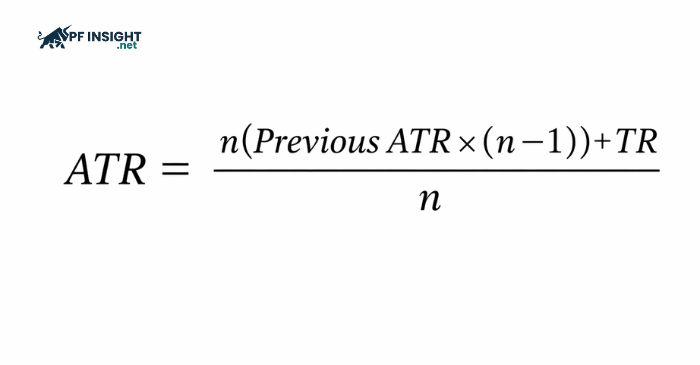

- When a previous ATR value already exists

Wilder used a smoothing method to make ATR more stable:

Trader-friendly interpretation:

- New ATR = mostly the old ATR + today’s TR added in

- So ATR reacts to new volatility, but without becoming too jumpy.

Step-by-step: setting an ATR stop loss properly

When applying Average True Range (ATR) volatility to stop-loss placement, the goal is not to avoid every stop-out, but to set a stop loss that “matches” current volatility. The better your stop loss fits volatility, the less likely it is to be hit by noise, while also helping you maintain consistent risk management discipline over time.

Step 1: Choose the right timeframe and ATR period

The first step is selecting the correct timeframe and ATR period. ATR should be read on the same timeframe you trade, so it reflects the volatility rhythm of your setup. For example, if you enter on H1, your ATR should be taken from H1, not ATR on D1 for an H1 stop. In terms of period, ATR(14) is the most common setting because it balances sensitivity and stability. If you need ATR to react faster, a shorter period may fit better, while a longer period will make ATR smoother and more stable.

Step 2: Use an ATR multiplier instead of a fixed distance

The next step is switching from fixed stops to volatility-based stops. Instead of placing a stop loss using a fixed pip/dollar distance, traders often follow the rule: “stop distance = ATR × k,” where k is a multiplier. The higher the multiplier, the wider the stop and the better it can withstand noise, but it also means you must reduce position size to stay within your risk limit. In practice, k typically ranges from 1.0 to 3.0 depending on the strategy and the market’s volatility.

Step 3: Place the stop beyond structure, then add an ATR buffer

A key point is that ATR should not be used as the only “coordinate” for stop placement. Your stop loss should still be based on market structure, such as swing lows/swing highs or the setup’s invalidation level. ATR then acts as an additional “buffer” so the stop is not placed too close to wick-heavy price zones. The correct approach is: identify where the setup is structurally invalidated, place the stop beyond that zone, then add an ATR-based volatility buffer. This helps the stop loss remain technically logical while also adapting to real market noise.

Step 4: Adjust position size to keep risk constant

Finally, ATR-based stop loss only works effectively if you also adjust position size. When ATR rises, the stop distance becomes wider. If you keep the same position size, your per-trade risk increases and your system loses control. Therefore, the rule is mandatory: the wider the stop, the smaller the position size must be, so your risk as a percentage of the account stays constant. This is why ATR is highly valued in risk management: it allows stop-loss placement and position sizing to “expand and contract” with volatility, rather than staying fixed based on emotion.

Recommended ATR stop-loss rules

ATR volatility helps traders move away from the mindset of setting stop losses using “one fixed number.” However, to apply it consistently, you still need a simple rule set to choose the right ATR period, define a reasonable stop distance, and reduce stop-outs caused by market noise. This section summarizes common, easy-to-apply principles with strong practical value.

Rule 1: Match your ATR settings to your trading timeframe

A fundamental rule is that ATR must reflect the volatility of the timeframe you trade. If you enter on H1, ATR should also be read on H1 to ensure your stop-loss distance matches the real swing rhythm of the setup. When traders use ATR from a higher timeframe to set stops on a lower timeframe, stops often become “misaligned” and lose consistency. ATR(14) generally fits most trading styles because it is sensitive enough to reflect volatility changes while remaining stable enough to prevent stop distances from fluctuating too erratically.

Rule 2: Use ATR as a volatility buffer, not a standalone stop level

A good stop loss is not determined by ATR alone. It must also be based on market structure. Stop-loss placement should start from the setup’s invalidation point (for example, below a swing low for a buy trade), then add an ATR buffer to avoid wick stop-outs. This is how traders reduce “false stop-outs” without making the stop unnecessarily wide and illogical. In other words, ATR allows the stop to “breathe” with volatility, while market structure ensures the stop is placed where the setup is truly invalid.

Rule 3: Choose ATR multipliers based on the volatility regime

The ATR multiplier determines whether the stop distance will be “tight” or “loose.” In low-volatility conditions where price moves smoothly, the stop does not need to be too wide. But when volatility rises, spreads widen, or wicks become more frequent, the stop should be widened accordingly. This is why fixed stop losses often fail: they do not adjust when the volatility regime changes. In practice, traders typically use a lower multiplier in low-noise conditions and increase the multiplier when the market shifts into a more volatile phase.

Rule 4: Keep risk constant by adjusting position size

Widening stops based on ATR only makes sense if you also adjust position size. When ATR rises, the stop distance increases. If you keep the same position size, your real account risk increases and losses become heavier during high-volatility periods. On the other hand, if ATR falls but you still keep a wide stop and small size, you lose capital efficiency. Therefore, the core rule is: stop-loss distance changes with volatility, while risk per trade must remain stable by adjusting position size.

Rule 5: Avoid over-optimizing multipliers without context

A common mistake is trying to find the “perfect multiplier” as if it were a fixed formula. In reality, the ATR multiplier should be treated as a flexible parameter depending on the market, timeframe, and price structure. A multiplier may work well during smooth trending conditions but perform poorly when the market shifts into a choppy range. Therefore, instead of over-optimizing, traders usually keep the multiplier within a reasonable range and prioritize system consistency, combining ATR with price structure to make stop-loss placement decisions.

ATR trailing stop vs fixed stop loss

After understanding how to use ATR volatility to set an initial stop loss, the next trade management question is: should you keep the stop fixed, or let it “move” with price? This is where an ATR trailing stop becomes a strong option to consider, especially for trend traders who want to maximize profits while keeping risk controlled.

What fixed stop loss does well (and where it fails)

A fixed stop loss is set once (usually based on market structure) and remains unchanged throughout the trade, unless the trader manually adjusts it as part of a plan. The biggest advantage of a fixed stop is simplicity and clarity: you know the setup’s invalidation point in advance and allow the market to “breathe” within that range.

However, fixed stop loss has one key limitation: it does not adapt when volatility changes during the trade. If the market suddenly expands in range, a fixed stop can become too tight and get taken out by a wick. On the other hand, if volatility contracts, a fixed stop can become too wide, making risk/reward less optimal and holding the trade less efficient.

How ATR trailing stop works

An ATR trailing stop addresses this problem by allowing the stop loss to adjust with volatility. Instead of keeping the stop in one place, the trailing stop “follows” price when the trade moves in your favor, while still maintaining enough distance to avoid noise.

In essence, an ATR trailing stop is based on a simple logic: the stop is placed at a distance of ATR × k from price, and it is updated in the trader’s favor when price makes a new high (for a buy trade) or a new low (for a sell trade). A very common variation is the Chandelier Exit, where the stop is calculated from the “extreme price level” since entry rather than from the current price. This allows the trailing stop to track trends better and reduces the chance of tightening too quickly.

The key point is: the higher the ATR, the “looser” the trailing stop; the lower the ATR, the “tighter” the trailing stop. This means it naturally adapts to volatility regimes without requiring constant manual intervention.

Why ATR trailing stops are powerful in trend trading

ATR trailing stops are especially effective when the market is trending clearly and expanding its movement range in the direction of the trend. In that case, the trailing stop helps you achieve two important outcomes.

First, it allows you to hold trades longer. Traders often exit too early due to fear of reversals or because they use fixed take-profit targets. A trailing stop shifts you from a “target-based take profit” mindset to a “let profits run with the trend” approach, while still providing a mechanism to lock in gains.

Second, a trailing stop reduces emotional interference. When the stop is updated using a volatility-based rule, you do not need to make constant decisions while the trade is running. This is crucial for building discipline and consistency in trade management.

When fixed stop loss can be better than trailing stop

Even though ATR trailing stops are powerful, fixed stop losses can still be better in certain situations. In reversal or mean reversion strategies, price often fluctuates around the entry zone before moving in the intended direction. In those cases, a trailing stop may tighten too early and stop you out due to short-term noise.

In addition, in sideways or intermittent-volatility markets, ATR trailing stops can get “knocked out repeatedly,” because the stop keeps updating while there is no clear trend. In this type of market, a structure-based fixed stop can sometimes be more stable.

Practical takeaway: how traders choose between the two

In practice, many traders do not choose strictly “one or the other,” but combine them in a process.

A common approach is to set the initial stop loss based on market structure with an ATR buffer, then once the trade has moved in your favor and cleared the noise zone, switch to an ATR trailing stop to protect profits. This method captures the best of both: the fixed stop helps the trade survive early volatility, while the trailing stop optimizes the “trend extension” phase.

In summary, fixed stop loss is strong for clarity and structural logic, while ATR trailing stop is strong for volatility adaptation and trend-based profit management. If your challenge is stop-loss placement and managing trades through changing volatility regimes, ATR trailing stop is a logical upgrade over keeping the stop fixed under all conditions.

Conclusion

Average true range volatility helps traders place stop losses in a way that better matches real market behavior, rather than applying one fixed stop level across all conditions. When you use ATR to “scale” your stop distance based on volatility and combine it with price structure, the likelihood of being stopped out by market noise is significantly reduced. As a result, you can manage risk more consistently and keep your trading strategy stable over time.